Navigating FDA Medical Device Classification: A Founder’s Guide to US Regulatory Pathways and Compliance

Medical device innovation moves fast. But product development demands more than ingenuity; it requires meticulous adherence to regulatory frameworks. For medical device startup founders and the biomedical engineering community, understanding the US FDA medical device classification system is non-negotiable. This isn’t merely a bureaucratic hurdle; it is the fundamental mechanism the FDA uses to align regulatory oversight with patient risk. Get it wrong, and market entry stalls.

This comprehensive guide outlines the critical aspects of FDA device classification, from the core risk-based classes (Class I, II, III) to the varied submission pathways (510(k) premarket notification, Premarket Approval [PMA], and De Novo classification). We will also touch on how emerging trends like Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), AI-enabled medical devices, and cybersecurity for medical devices are reshaping the regulatory landscape.

Our goal here is to equip you with a robust framework for strategic regulatory planning. Knowing your device’s classification early informs design, testing, and documentation requirements. This proactive approach minimizes delays, controls costs, and most importantly, ensures patient safety.

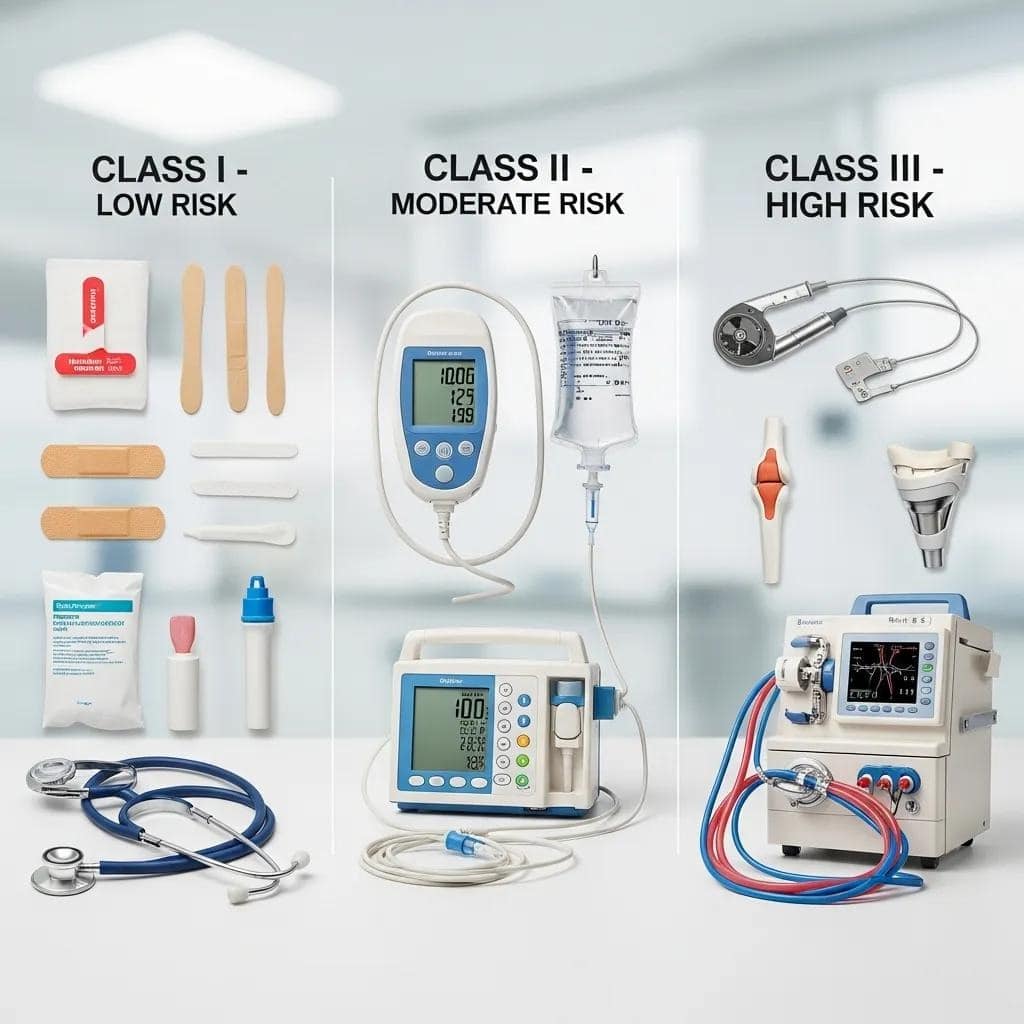

FDA Medical Device Classes: Risk and Control Scale

The FDA employs a risk-based classification system. This means the potential for harm to a patient or user directly dictates the level of regulatory control.

Devices are categorized into three classes:

Class I (lowest risk), Class II (moderate risk), and Class III (highest risk). Each class carries distinct regulatory obligations.

This tiered approach, outlined in the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR Part 860), ensures an appropriate balance between promoting innovation and safeguarding public health.

Consider the distinctions below. These classifications directly inform your chosen medical device regulatory pathway and influence project timelines and resource allocation.

| Device Class | Typical Risk Level | Required Controls | Typical Pathway | Example Devices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Low risk | General Controls (registration, labeling, QMS basics) | Often exempt from premarket submission | Bandages, tongue depressors |

| Class II | Moderate risk | General Controls + Special Controls (performance standards, guidance) | 510(k) premarket notification | Infusion pumps, diagnostic catheters |

| Class III | High risk | PMA-level controls (clinical evidence, manufacturing controls) | Premarket Approval (PMA) | Pacemakers, heart valves |

This framework clarifies that a device’s risk profile drives both the required controls and the subsequent submission strategy. We delve deeper into each class next.

Class I Medical Devices: General Controls and Simplicity

Class I medical devices present the lowest potential for harm. Assurances of their safety and effectiveness are typically achieved through applying general controls.

These foundational controls, mandated for all medical devices regardless of class, include:

- Establish registration with the FDA.

- Device listing with the FDA.

- Adherence to Quality System Regulation (21 CFR Part 820) basics, such as complaint handling and recordkeeping.

- Proper labeling and instructional requirements.

- Reporting of adverse events.

Notably, many Class I devices are exempt from certain premarket requirements, like the 510(k) submission. This exemption can expedite time-to-market. However, fundamental obligations like correct labeling and adverse event reporting remain.

The specific exemptions vary significantly by product code and regulation. Understanding these details is crucial. Simple consumables, like elastic bandages or examination gloves, exemplify this category. Their minimal patient interface and established safety profiles justify a less burdensome oversight.

Class II Medical Devices: Balancing Risk with Special Controls

Class II medical devices pose a moderate risk to patients. Beyond general controls, they necessitate special controls tailored to mitigate specific identified risks, ensuring reasonable safety and effectiveness. These special controls can take various forms:

- Performance standards.

- Postmarket surveillance requirements.

- Specific guidance documents published by the FDA.

- Recommended testing protocols.

- Unique labeling requirements.

For most Class II devices, the regulatory pathway involves a 510(k) premarket notification.

Here, manufacturers must demonstrate substantial equivalence to a legally marketed predicate device. Addressing special controls often involves rigorous bench testing, medical software validation (if applicable), and sometimes limited clinical data.

Think of devices like infusion pumps or many types of diagnostic catheters. Their direct interaction with patients, or their diagnostic function, requires predefined performance metrics and robust risk controls. A clear understanding of applicable special controls is vital for designing effective test plans and minimizing delays during FDA review.

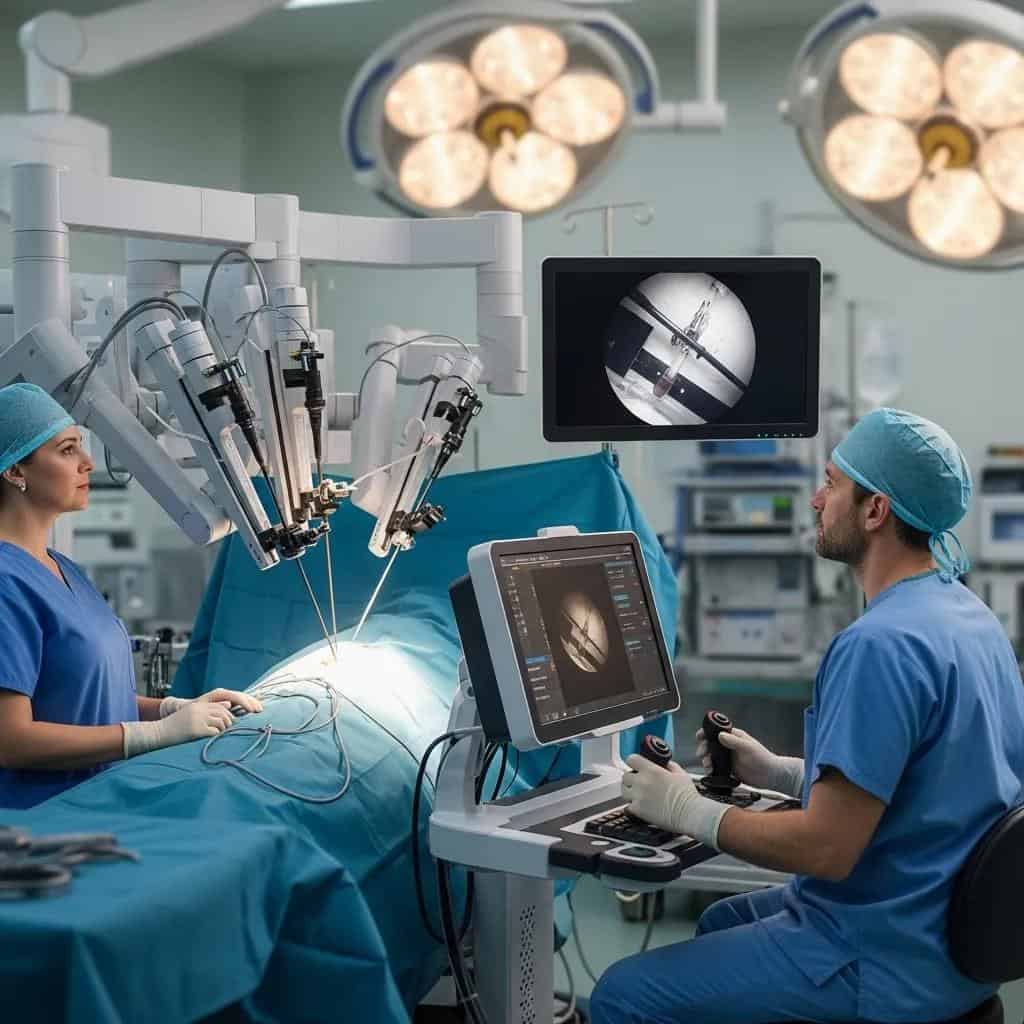

Class III Medical Devices: Stringent Review for High Risk

Class III medical devices represent the highest risk category. These are typically life-sustaining, life-supporting, or implantable devices, or those with entirely novel technology where safety and effectiveness cannot be assured by general and special controls alone. They demand the most rigorous scientific and regulatory review.

The primary pathway for Class III devices is Premarket Approval (PMA). This process requires comprehensive clinical evidence, often involving extensive, well-designed clinical trials. Manufacturers must submit detailed data on manufacturing controls, validated processes, full labeling, and thorough risk analyses.

Post-approval surveillance commitments are also a common expectation. The PMA pathway is exhaustive, costly, and time-consuming, often involving FDA advisory panels and extended dialogue with the agency.

Integrating regulatory strategy with clinical study design from the earliest stages of development is paramount for manufacturers pursuing this pathway. This integrated approach can reduce regulatory uncertainty and ensure successful market access and long-term compliance. Pacemakers and prosthetic heart valves exemplify Class III devices.

The Classification Process: Intended Use is King

The journey to FDA clearance starts with classification. This process is not arbitrary; it’s driven by specific criteria.

First, define your device’s intended use and indications for use. This is the most critical step. Intended use describes the general purpose of the device, while indications for use specify the particular diseases or conditions the device diagnoses, treats, prevents, or mitigates, along with the target patient population.

A subtle shift in this wording can profoundly impact classification. For example, a device intended solely for in vitro diagnostic monitoring might be Class II. The same device making therapeutic claims could be Class III. Precision in these statements is key.

Next, manufacturers must:

1. Search the FDA Product Classification Database: This online tool is invaluable. Use your device’s intended use, technological characteristics, and keywords to identify existing product codes, regulatory classifications (21 CFR parts), and any specific guidance documents or special controls.

2. Identify Predicates: For Class II devices, finding a substantial equivalence predicate is crucial for a 510(k). This involves comparing your device to one already on the market regarding intended use, technological characteristics, and safety/effectiveness profiles.

3. Determine the Regulatory Pathway: Based on risk, intended use, and predicate availability, select the appropriate pathway: 510(k), PMA, or De Novo.

Regulatory panels and specific 21 CFR classifications provide the legal framework for these decisions, dictating testing expectations and control requirements. A clear, documented decision process reduces ambiguity and strengthens your submission. As Kelsey Lee, a RAPS-Device certified regulatory consultant, often emphasizes, thorough preliminary classification work saves immense time and resources down the line.

Navigating the FDA Product Classification Database: A Workflow

Effectively using the FDA Product Classification Database is a skill. Here’s a practical workflow to guide your search:

1. Initial Search: Start with concise phrases describing your device’s intended use (e.g., “in vitro glucose measurement,” “surgical guide”). This should provide an initial list of potential product codes and associated regulatory panels.

2. Refine Keywords: Add technical keywords relevant to your device (e.g., “electrochemical sensor,” “implantable,” “medical software”). This narrows results, leading to more specific regulation (21 CFR) citations.

3. Review Product Code Details: Click on relevant product codes. Examine the classification date, statutory authority, and crucially, any referenced special controls or guidance documents.

4. Predicate Research: If a 510(k) is likely, look up 510(k) summaries or De Novo decision summaries for similar devices. These offer insights into evidence types and testing protocols accepted by the FDA.

5. Document Everything: Maintain records of your search terms, the rationale behind your chosen classification, and any alternative classifications considered.

For ambiguous cases, a pre-submission meeting with the FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) can provide invaluable clarity and validate your classification choice before a formal submission. This early engagement can prevent costly missteps.

Key Regulatory Pathways: 510(k), PMA, and De Novo

Understanding the distinct features of the FDA medical device regulatory pathways is fundamental. Your device’s classification directly dictates which path you must take.

| Pathway | When Used | Key Requirements | Typical Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| 510(k) Premarket Notification | Device has a suitable predicate; usually Class II | Demonstrate substantial equivalence via bench testing, performance data, and sometimes clinical data | 3–6 months typical review |

| Premarket Approval (PMA) | High-risk Class III devices or novel life-supporting devices | Clinical trials, comprehensive manufacturing and quality data, labeling, and post-approval commitments | 12–36 months typical review |

| De Novo Classification | Novel low-to-moderate risk devices without a predicate | Risk-based evidence package to establish new classification and special controls | 6–12 months typical review |

Choosing the correct pathway early is critical. It shapes your entire development process, including clinical study design, bench testing plans, and overall submission timelines.

The 510(k) Premarket Notification: Demonstrating Equivalence

A 510(k) premarket notification is the pathway for many Class II devices and some non-exempt Class I devices. The core principle here is demonstrating substantial equivalence to a legally marketed predicate device. This means your new device must have the same intended use and similar technological characteristics as the predicate. If there are differences, they must not raise new questions of safety or effectiveness. Any such differences need to be addressed with robust data.

A comprehensive 510(k) submission typically includes a detailed device description, proposed labeling, results from bench and performance testing, medical device software validation (if applicable), biocompatibility data, and sterilization validation, all clearly mapped to the predicate device’s characteristics and performance. Common pitfalls often involve insufficiently clear intended use statements, inadequate performance data, or failure to thoroughly address identified special controls. Proactive engagement and meticulous preparation can significantly reduce the likelihood of additional information requests, which often delay review timelines.

Premarket Approval (PMA): The Gold Standard for High-Risk Devices

The Premarket Approval (PMA) pathway is the FDA’s most rigorous. It is reserved for most Class III devices, those where general and special controls alone cannot assure safety and effectiveness. A PMA submission demands a robust body of evidence.

This typically includes:

-

- Extensive, well-controlled clinical trials demonstrating efficacy and safety.

-

- Detailed information on the device’s design and manufacturing processes, including adherence to good manufacturing practice (GMP).

-

- Comprehensive quality assurance data.

-

- Complete labeling.

-

- Thorough risk analysis documentation.

Commitments for postmarket surveillance to monitor device performance once on the market. - Extensive, well-controlled clinical trials demonstrating efficacy and safety.Detailed information on the device’s design and manufacturing processes, including adherence to good manufacturing practice (GMP).

- Thorough risk analysis documentation.

Given the substantial timelines and financial investment required for PMA, integrating the regulatory strategy with early clinical study design is critical. This ensures all collected data aligns with FDA expectations from the outset. Successful PMA planning reduces regulatory uncertainty and facilitates long-term market access.

The De Novo Classification Pathway: For Novel Low-to-Moderate Risk Devices

The De Novo classification pathway offers a route for truly novel devices that lack a legally marketed predicate and cannot be classified into Class I or II through a 510(k) process, but also do not warrant Class III (PMA) status. These devices must be demonstrably low-to-moderate risk.

De Novo eligibility hinges on proving two key points:

A De Novo submission typically contains a strong rationale for the proposed classification, a detailed risk analysis, comprehensive performance testing results, and sometimes supporting clinical data. Proposed special controls and draft labeling are also essential components. Thorough organization and early engagement with the FDA via pre-submission meetings can significantly improve clarity and the likelihood of acceptance:

-

- No legally marketed predicate device exists.

-

- The device’s probable benefits outweigh its probable risks, and general controls coupled with proposed special controls can provide reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness.

A successful De Novo classification is a significant achievement. It establishes a new device classification, setting the precedent and defining the regulatory controls for that device type. This new classification then serves as a predicate for future 510(k) submissions of similar devices.

Case Studies: Lessons from De Novo Approvals

Examining past De Novo approvals offers valuable lessons. For instance, a novel diagnostic assay for a specific disease indication achieved De Novo clearance after extensive analytical performance studies and clinical concordance data. The key was carefully defined labeling reflecting the evidence presented.

Another example, a wearable monitoring device, combined robust bench testing with a targeted clinical usability study to validate sensor accuracy and patient safety. These cases underscore that tailored evidence, pragmatic special controls, and early FDA engagement are crucial elements for success. Applicants must clearly articulate the device’s benefit-risk profile and ensure postmarket plans address any residual uncertainties identified during the review.

Recent Trends Shaping FDA Medical Device Classification

The regulatory landscape is dynamic, with recent (2023–2024) developments significantly impacting FDA medical device classification. Manufacturers must pay close attention to updates concerning software, AI, and cybersecurity in particular.

AI, SaMD, and Cybersecurity: New Challenges, New Guidance

The rapid evolution of medical software and AI-enabled medical devices presents unique classification challenges. Software often alters function and risk without hardware changes. The FDA’s guidance for Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) and AI/ML emphasizes several key aspects:

Intended Use: The clinical purpose and decision-making role of the software are paramount in classification.

Algorithm Transparency: Understanding how AI algorithms function, especially for adaptive AI/ML systems.

Real-World Performance Monitoring: Postmarket data collection and analysis are increasingly important.

Validation and Bias Assessment: Ensuring AI algorithms are validated, and potential biases are identified and mitigated.

Update/Change Management: Robust processes for managing changes and updates to AI/ML software.

For cybersecurity for medical devices, expectations have tightened considerably. The FDA now requires manufacturers to incorporate threat modeling, secure design principles, and comprehensive postmarket vulnerability management into their premarket submissions and risk analysis documentation.

Practical steps for manufacturers include detailed documentation of algorithm training datasets, implementation of robust software lifecycle processes, and developing postmarket monitoring strategies that align with FDA guidance on SaMD and cybersecurity. This proactive approach helps reduce regulatory uncertainty.

The Impact of FDA Public Comments on Class I Accessories

The FDA’s public comment processes offer valuable insights into potential regulatory shifts. The December 2023 comment period on Class I accessories, for instance, signals a potential re-evaluation of how these low-risk components are regulated. Should accessories be more explicitly defined as Class I with specific controls, manufacturers might face altered obligations for labeling, registration, and potentially new special controls.

Manufacturers are well-advised to monitor public dockets, submit reasoned comments when appropriate, and prepare contingency plans for potential reclassification. Remaining agile and ready to adjust product claims or documentation ensures ongoing regulatory compliance.

Global Context: FDA vs. EU MDR Classification

For manufacturers targeting international markets, understanding the distinctions between the US FDA medical device classification system and other global regulatory systems, notably the European Union Medical Device Regulation (EU MDR), is critical. While both aim to ensure device safety and effectiveness, their approaches differ significantly.

Key Differences Between FDA and EU MDR Classification

The FDA system, as discussed, relies heavily on intended use and the concept of predicate devices for many classifications. The EU MDR, conversely, employs a more prescriptive, rule-based classification system. These rules, detailed in Annex VIII of the MDR, often lead to devices being assigned a higher risk class in Europe compared to the US. This difference can profoundly impact the required evidence package.

For example, a device cleared via a US 510(k) (typically Class II) might require substantial additional clinical data to meet EU MDR’s stringent clinical evaluation requirements and achieve conformity assessment via a notified body. Labeling and postmarket surveillance obligations also often differ in scope and detail between the two jurisdictions.

The practical implication is that manufacturers pursuing both markets should design their clinical studies and quality management system (QMS) processes to meet the stricter of the jurisdictional requirements where feasible. Documenting the rationale for any region-specific adaptations is also crucial for smooth approvals.

Global Harmonization Efforts and Their Influence

Global harmonization initiatives, such as those by the International Council for Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) and various international standards development organizations (e.g., ISO 13485 for quality management), aim to converge technical requirements, clinical data expectations, and quality system approaches worldwide. These efforts, while incremental, simplify cross-border regulatory strategies and reduce redundant testing.

Harmonized guidance on topics like combination products, clinical evidence transparency, and cybersecurity provides consistent baselines that regulators in different regions often reference. However, complete convergence remains a distant goal, and jurisdictional interpretations will always retain some degree of variation.

Manufacturers should actively monitor these harmonization outputs and integrate internationally recognized standards into their design controls and clinical planning. This strategy can yield the widest regulatory benefit and streamline global market access.

Practical Steps for Medical Device Manufacturers

Navigating the complexities of FDA medical device classification might seem daunting, but a structured approach can demystify the process.

Practical Next Steps:

Clarify Intended Use: Begin every project with a clear, concise statement of your device’s intended use and indications for use. This single step is the foundation for all subsequent regulatory decisions.

Systematic Database Search: Utilize the FDA Product Classification Database thoroughly. Document all search terms, product codes reviewed, and your rationale for choosing a particular classification or pathway. This documentation is invaluable for internal records and potential regulatory inquiries.

Choose the Right Pathway: Select the appropriate regulatory pathway (510(k), PMA, De Novo) based on a diligent assessment of your device’s risk profile and the availability of suitable predicates. Do not try to force a fit.

Top Compliance Priorities:

Focused Test Plans: Develop test plans that directly address the special controls and identified risks for your device’s classification. This ensures collected data is relevant and efficient.

Integrate Cybersecurity & Software Lifecycle Controls: For all software-enabled devices, especially SaMD and AI/ML, embed robust cybersecurity and software development lifecycle controls early in the design process. This is no longer an afterthought; it is a fundamental design requirement.

Engage the FDA Early: For novel devices, those with ambiguous classifications, or complex technologies, consider leveraging pre-submission meetings with the FDA. Such interactions offer invaluable feedback and can significantly de-risk your regulatory journey.

Successfully bringing a medical device to market requires a deep understanding of the regulatory landscape. By diligently applying these principles and staying informed on evolving guidance, medical device startup founders and the broader biomedical engineering community can confidently navigate the FDA’s classification system, ensuring innovative solutions reach patients safely and efficiently.